Riders hate surprises. Well, the unexpected birthday party might be okay, but on a motorcycle, surprises are bad. On this day, on this bike, at this speed, in this corner, on this line, with these tires at these pressures, in this heat, wearing this helmet and these gloves, we want to know what the motorcycle will do in the next few seconds. We want this kind of knowing over and over because it’s a long trail ahead.

This month the MotoSafe article is about the dirty secrets of risk management. Dirty because we are going off-pavement, but even if you don’t ride a GS, read on because there will be times when all riders have to deal with less-than-perfect conditions. You may encounter an unpaved detour, for example, or a construction zone. The mental skills we use off-road work well in traffic, too.

THE NEXT FEW SECONDS

We can’t know exactly what your bike is going to do in the next few seconds, but we can make an educated guess about what will happen. Using an “if – then what?” decision process, we collect information about the trail ahead and draw conclusions about what might happen under certain circumstances. Please notice I said conclusions about what might happen next. This is because you have choices, and each one can lead to a different outcome. Riding safely is being able to see the choices ahead, picking the best one and then making it happen. Risk management is a form of educated guessing.

THE THREE-LEGGED STOOL

Most professional riders and their coaches know that specialized training improves decision making at speed. We often visualize this sort of training as a three-legged stool. The seat of the stool represents traction. Without it, we can’t go, stop or turn. Each leg of the stool is critical; if one breaks, the stool falls and traction is lost. The three legs are: 1) control function; 2) body position; and 3) decision making. The first two are for later articles, but the third leg is our current subject – how to make good decisions to reduce risk.

Whatever the speed of your motorcycle, your decision making has to be faster. One way to make faster decisions is to reduce how much you have to think about before you start moving. In other words, confirm as much information as possible in advance so issues don’t pop up as random thoughts to distract you at speed.

PRE-FLIGHT CHECKS

All riding decisions are made in context, meaning your current situation. Before you let the clutch out, take a deep breath and do a quick assessment. Here are some common examples of things to think about before you go:

- Comfort level: Am I ready for what’s ahead. If nervous, why? What are my limits today?

- Physical condition: Am I fit and ready? A little sore? Where? What do I need to do?

- Power to weight: Panniers overflowing? One-up or two? Single or twin? Shock settings?

- Surface: Hard-packed or soft? Most likely both. Where will they change? Tires? Air?

- Conditions: Hot and dry? Cold and wet?

- Maintenance: Did I check my oil? Chain? Fuel level? Water? Tools? Tire kit?

- Navigation: Maps, roll chart or GPS? SPOT receiver turned on?

- Unexpected: If an emergency happens, what do I have to deal with it? Phone charged? First aid kit aboard?

Doing a pre-flight check will increase your comfort level by reducing the number of things you have to think about while on the road or trail.

One more thing before you leave: Riding a motorcycle is an athletic endeavor. That makes you an athlete every time you ride. Please don’t enter the game cold. Just like your tires, your performance as a rider will be down until you warm up. Take a minute to do some stretching and light range-of-motion exercises. After you have ridden a while and are taking a break, do some light strengthening exercises before you get back on. Visualize yourself as an athlete in training.

RISK TOLERANCE

You’re warmed up and have done some miles. The hill in front of you is steep and rutted. You have a choice to make: Try to climb it, find a way around it or go back. Of course, you can always do nothing, but you didn’t bring your sleeping bag. How will you decide what to do?

Many riders use a mental teeter-totter approach. They put the risk factors on one end and their skills (and their bike’s capabilities) on the other. If the teeter-totter tips down towards risk, it’s too dangerous and they turn back or go around. If the mental teeter-totter tips down on the ability end, then they climb the hill.

When risk and ability are in balance, you have to look at how much risk you’re willing to accept. In training, we have a very low risk tolerance threshold – we don’t want students to get hurt. The other end of that scale is racing, and sometimes you have to roll the dice to earn a podium finish. Most riders are somewhere in the middle.

RIDE YOUR OWN RIDE

Each rider has their own risk management teeter-totter, their own risk tolerance, their own set of unique strengths and weaknesses. This is where some GS club rides go astray. Just because you all ride the same motorcycle brand and model doesn’t mean you all should make the same decisions about degree of difficulty or pace. There are just too many variables.

Unlike you, the guy in front may have a garage full of motocross bikes and the know-how to use them. The rider in the lead may have remembered to let some air out of her tires and you didn’t. Peer pressure means doing what your ride buddies do, even if you don’t want to. Ego means riding over your head to save face.

Going too fast to hang with the others has led to many crashes and injuries. Being strong enough to say no and backing off are important parts of risk management. Besides, you don’t want your memories of the day to be of the butt that was in front of you or the dust in your nose. Ride your own ride.

BE SMART

Risk-benefit analysis may not work if you are under the influence of alcohol. A great rule of thumb is EIGHT HOURS FROM BOTTLE TO THROTTLE. Prescription drugs can also impair your judgment. When you are dehydrated or fatigued, your ability to assess risk changes for the worse. Ride healthy and wear full protective gear every time you throw a leg over the seat.

KEEP IT SIMPLE

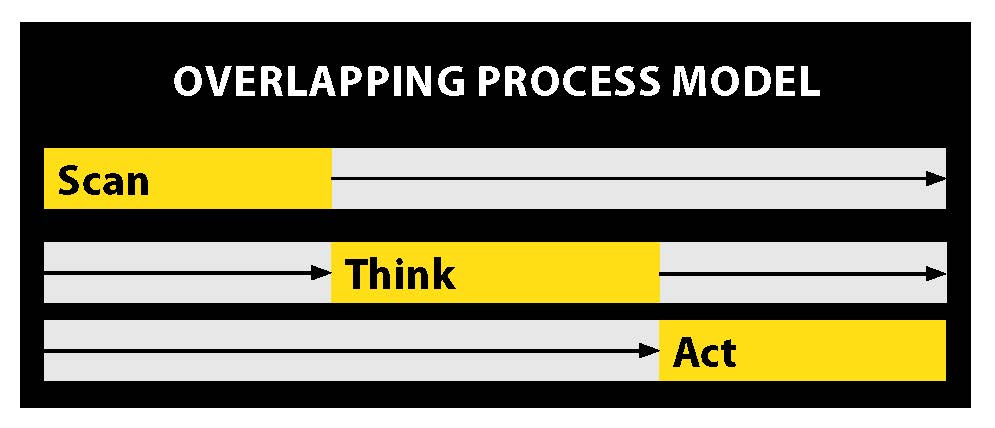

Decision making at speed needs to be easy and fast. Things happen quickly, even in the lower gears. In previous MotoSafe articles, you learned the Motorcycle Safety Foundation has streamlined its recommended decision making system. The old SIPDE (scan-identify-predict-decide-execute) is now simply SEE (search-evaluate-execute). The SEE acronym describes a three-step speed management system that has been used successfully by racers for decades. Using simple action verbs, here’s what happens inside the racer’s helmet.

STEP 1: SCAN

Collecting information about what’s ahead is called scanning, a form of eye patterning. Scanning means to look around in a repetitive pattern of focus points. For example, head up, eyes level to the horizon: Look ahead just over the clutch lever, then straight ahead at 20 feet, then straight ahead at 100 feet, then just over the right brake lever. Repeat.

This is only a simple example, as most scanning patterns have more than four focus points and sight distances are speed related. Eventually scanning becomes a comfortable habit, a practiced dance of eye movement. Going off pattern for a split second for turn markers, braking points or the unexpected is normal; just get back on pattern quickly. Keep those eyes moving.

As you scan, you’ll pick up surface changes like braking bumps (washboard ruts), rocks or other hazards. You’ll also see pitch changes, ups, downs, side hills or whoops. You’ll sense traffic – the bike showing a wheel to your side or cars on the road. Collect all information possible as snapshots, then move to Step 2 – but keep scanning as you do.

STEP 2: THINK

Sort the trail information into options. I can go here, downshift there and attack – or I can brake and turn – or I can STOP! Rank the options in order of outcome. The best outcome is usually the best choice of what to do. Your second-best option is usually your back-up plan just in case. As you move to action, start the next round of evaluation.

STEP 3: ACT

Make it happen – NOW! If your motorcycle has become an extension of your body through training, conditioning and experience, your control response and body mechanics happen almost instantaneously. If you’re just learning, slow down or even stop if you need more time. Speed may be fun, but it is not always your friend. Evaluate how it’s going and be ready to make adjustments or go to your back-up plan.

OVERLAP AND REPEAT

All three steps continuously overlap. As long as the bike is moving, you are scanning. While scanning, you are continuously deciding on your next move. While you are acting, you are already processing new trail information (scanning) for the next round. It’s an endless circle of mental and physical multitasking.

The reason a three-step decision making process works is because of how the human mind and body connect. Step 1 is called perception. This is the time it takes for the eyes to send a message to the brain. In the beginning, average perception time is about 0.75 of a second per visual focus point. At 30 mph, you will travel about 44 feet – a long time to be looking in one place at speed.

On a motorcycle this is almost focus fixation, when a rider looks at one point too long and misses important information at other points. Fortunately, perception improves with experience, training and conditioning. You get faster because you know what to expect from various conditions.

Step 2 is called reaction. For the average person, reaction time is also about 0.75 of a second. In other words, it takes about 0.75 seconds to perceive and another 0.75 seconds to react. At 30 mph, you will have traveled about 88 feet from the time you see a rock to the time you start steering around it, if you’re average. Your goal is to become faster than average – much faster.

HARD EYE – SOFT EYE

Racers train to scan at less than 0.5 seconds per scanning point. They also learn to scan at multiple points at one time using a technique called Hard Eye – Soft Eye (HESE). HESE means to become skilled at continuously processing two visual signals in the brain at the same time, one clear and detailed visual picture from the center of the eye (foveal vision), and a second – less distinct – picture from the edge of your eyes (peripheral vision).

For example, on a track at speed, you clearly see the jump face 100 feet ahead and at the same time glimpse the front wheel edging ahead on your right. Most people have foveal and peripheral vision, but motorcycle riders need to develop it and use it at a much higher level.

Until you become proficient at using two sight pictures, practice on a busy track or riding in difficult terrain can be hazardous. A simple way to hone your sight skills is to sit in a chair and watch television. While you are enjoying the program, count the number of books on the shelf off to the side of the room. If not books, count something else. When you can easily follow the storyline on the television and precisely remember the numbers at the same time, try it again wearing your helmet and goggles. It will look funny for sure, but do it anyway.

When you are ready, try it on the bike – and go slow at first. Work your way up to speed and complex detail. Imagine the desert racers looking way ahead for turn makers at 80 mph and watching for sand ruts or rocks just ahead of the front wheel. That’s HESE in action.

SPEEDING UP THE PROCESS

When first learning to ride, we sometimes use a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. That’s the part genetically programmed for survival in life-threatening situations, sometimes called fight or flight. That’s why we have novice students cover the levers with four fingers. If they panic, they squeeze both levers, controlling power and stopping the bike as they hang on.

In training, we teach riders to move their decision making to a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex. Decisions made there are not based on a survival instinct, but rather on something called executive function. We train riders to be proactive rather than reactive. They learn to collect and process information, rank options and pick the best course of action. If they use executive function long enough, it can become automatic. This happens after enough practice to create muscle memory and a reflex-like thought process in a part of the brain called the medulla oblongata.

"Eight Hours From Bottle To Throttle"

We train and condition to create this state of performance awareness. Scanning, ranking and acting become almost an unthinking habit. Athletes call this form of predictive motor control being in the zone or more simply, flo. Riding with flo is to ride well, with minimal physical and mental energy expenditure. In flo, perception times are reduced and reaction times are faster. It is the reward for all the hard work (training) you’ve put in. In flo, your motorcycle becomes an extension of your body – the ultimate goal of training.

EXERCISE FOR THE MIND

On a practice course, I will ask riders to do slow speed counterbalance turns around a circle of orange traffic cones. As they are working on body mechanics and control functions, I ask them to count the number of cones in the circle. To make it more challenging, I will set up different sizes of circles on the range to be taken in a set order. The riders must do the circles properly, in order, and remember the number of cones in each circle.

For racers, I will set cones on the inside and/or outside of high-speed turns. The riders must do the turns well and tell me the number of cones for each turn after each practice session. In more advanced classes, I sometimes place cones on the backside of jumps or stand by the side of the track/trail and hold up a number of fingers to be counted at speed or in mid-air as the riders go past. The training goal is to learn to use Hard Eye – Soft Eye scanning patterns at whatever speed and in whatever condition or situation they are riding in.

MORE TO LEARN AND DO

We have only scratched the surface of predictive motor control; there is so much more to learn and to do.

Remember the three-legged stool? What does yours look like? Are all three legs fully developed and in balance? If not, then maybe it’s time for more reading or to take a class or two. No matter where or how you train, keep at it, because safe riding is like a muscle. It needs constant exercise to stay strong.

About the Author

Ramey “Coach” Stroud is a former off-road racing champion, past motocross rider of the year and an around-the-world motorcycle traveler. He was awarded the BMW MOA Foundation’s Individual of the Year award for his motorcycle training programs and contributions to rider safety. You can learn more about him at his website, RIDECOACH.COM.

Originally published in BMW Owners News in February 2013.

Photo by Gerhard Siebert on Unsplash

Photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash