Pilots use the international phonetic alphabet, and therefore understand immediately the meaning of the term “sierra alpha.” It is code for SA, which is the acronym for situational awareness. Motorcyclists with more than about 5,000 miles understand the concept, but not necessarily the terminology. The individuals most acutely sensitive to situational awareness are fighter pilots. Fighter pilots have a saying: “Speed is life, altitude is insurance.” This is certainly accurate to some extent, but if your enemy is approaching, neither speed nor altitude will help!

One way to gain some perspective on this is to visualize that you are operating your motorcycle in an environment where just about everyone around you is trying to kill you. Sounds like a fighter pilot’s environment, doesn’t it? Flying a fighter and riding a motorcycle both require constant situational awareness for survival. Perhaps we should settle on a definition of situational awareness before we proceed.

Situational awareness is characterized in a Wikipedia entry as:

- Perception of elements

- Understanding the significance of each element

- Using that understanding to predict a future situation

According to the Naval Aviation Schools Command, situational awareness refers to the degree of accuracy by which one’s perception of his current environment mirrors reality.

Perception vs. Reality

- View of situation

- Incoming information

- Expectation and biases

- Incoming information vs. expectations

Factors that reduce situational awareness

- Insufficient communication

- Fatigue/stress

- Task overload

- Task underload

- Group mindset

- “Press on regardless” philosophy

- Degraded operating conditions

As you can see, the two are very similar, with the naval aviation description being a little more technical and more oriented toward military aviation. Clearly, the parallels between operating an aircraft and riding a motorcycle are considerable. Since the first description is somewhat more concise and generic, let’s explore it in more depth to see what we can learn.

PERCEPTION OF ELEMENTS

Our perception of the elements is more than just what we see. It is a mental photograph of what is going on all around us, mostly derived from what we perceive visually. It also includes our ears, skin and even our nose, as they provide input as to elements of our situation. Our visual perception is dependent upon the way we scan for visual cues. Although everyone does this, few really understand how they do it, and even fewer have a conscious, methodical process for accomplishing a good visual scan.

Again, we relate this to flying, and again the parallel is clear. Aviators are taught to scan the instruments and the sky around them. It begins as a set pattern during training, but as the pilot gains experience, he or she modifies the scan pattern to incorporate new instruments, equipment or situations into the pattern.

Here is an example of a scan pattern for flying aircraft. For those unfamiliar with aircraft instruments, the nose attitude indicates the airplane’s orientation relative to the ground – i.e., nose up or down or bank angle. The pattern usually goes like this:

Nose attitude – airspeed – nose attitude – altimeter – nose attitude – turn needle/ball – nose attitude – compass – nose attitude – navaid – nose attitude – vertical speed indicator – nose attitude – airspeed – nose attitude – altimeter – and so on, repeating itself over and over with only enough time spent on each item to quickly grasp what it is telling us.

A glance is usually enough. As you can see, nose attitude is the primary source of information and the scan constantly returns to it for reference. The frequency with which each item comes up indicates its importance to the pilot. Since even minor changes in attitude, airspeed or altitude can change the readout on virtually every instrument in the cockpit, each one has to be scanned every few seconds. If you add to this the necessity to scan the sky in all directions, you can easily see why fighter pilots have strong necks!

This type of scan is almost exactly how successful motorcycle riders obtain their perception of elements. Depending on the rider, it probably boils down to something like this when on a multi-lane highway in traffic:

Road ahead – Zone Right – road ahead – Zone Left – road ahead – speedometer – road ahead – right mirror – road ahead – left mirror – road ahead, and so on.

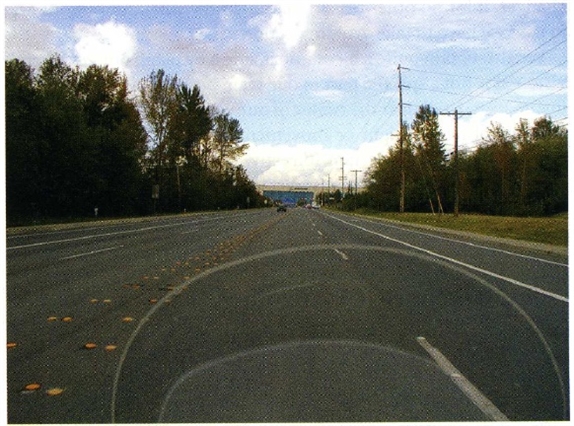

Clearly the road ahead is the primary source of information for the motorcyclist. This is one reason we are taught to keep our head up and eyes down the road. As taught in basic riding courses, you will travel in the direction your eyes are looking. For this reason, your primary scan item should always be that portion of the road ahead, where you expect to be in two to four seconds. This requires looking well ahead in a curve, although it does not mean that other parts of the scan can be ignored. Photograph A provides a general idea of the primary scan items for a motorcyclist on a city street. The two boxes represent Zone Right and Zone Left.

Photograph A

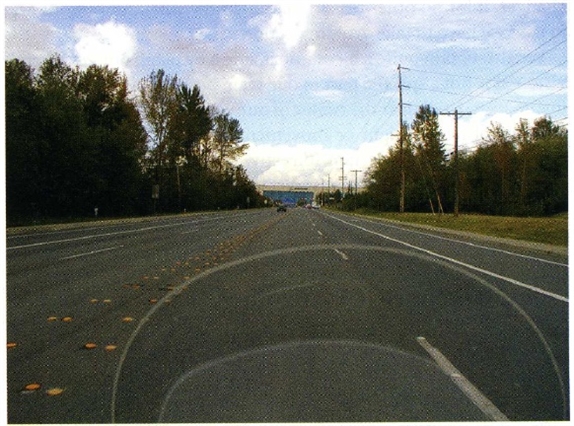

The zone portion of the scan will vary in size depending on speed, visibility to the side, how fast an object is expected to approach from the side and what peripheral vision tells the rider. As you can see in Photograph B, on a four-lane highway, the zones would include those portions of the lanes on either side and ahead of the motorcycle. Zone Left might include oncoming traffic if there is no barrier. However, on a multi-lane highway, it would also include any traffic moving in the same direction as the motorcycle in the left lane ahead. Zone Right would include the shoulder and any traffic moving the same direction as the motorcycle in the lanes to the right.

Photograph B

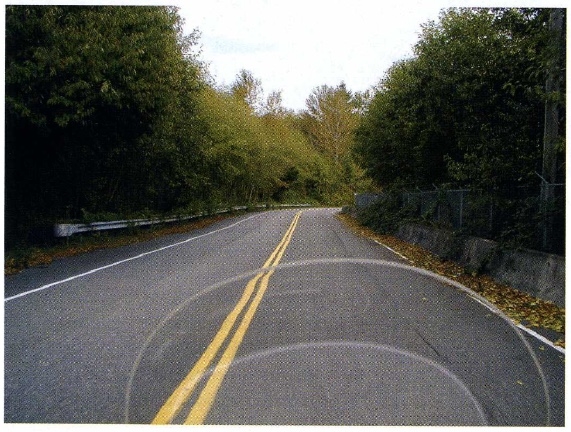

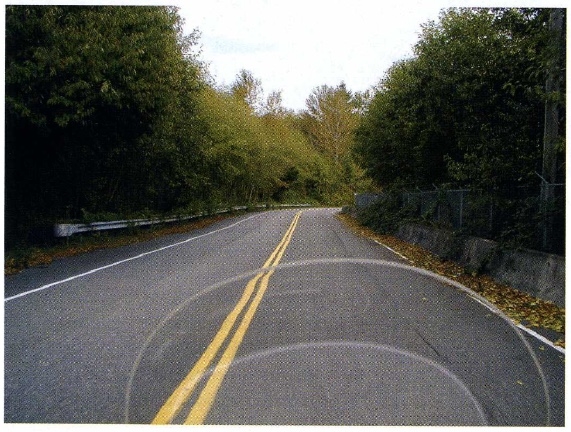

On a two-lane road such as shown in Photograph C, Zone Left would include the oncoming lane and traffic in it, plus the left shoulder and any roads coming from the left. Zone Right would include the shoulder and roads on the right. In this case, with a fence on the right shoulder, there is relatively little that can present a danger; therefore, that area wouldn’t be scanned as frequently until the fence is no longer there. As we reach the curve or the end of the fence, our scan again includes increased Zone Right canning in order to see any hazards well before they cause us serious problems.

Photograph C

Part of the rider’s perception of elements should be knowledge of what vehicles are behind and nearby, and particularly any vehicle with an overlap that would prevent a lane change. This requires checking the mirrors frequently. A normal lane change would dictate a head check prior to executing the maneuver. However, an emergency lane change or stop would not allow the time to do a check. The rider’s mirror scan should provide continual knowledge of what vehicles are in the zone from four o’clock to eight o’clock. If the rider knows from a previous mirror scan that a vehicle is there, there may be no option to change lanes. However, if the rider has not seen a vehicle there in the last several mirror checks, the slim possibility of contacting a vehicle going the same direction might be preferred to hitting one head on.

Needless to say, every few minutes, the rider adds to his or her scan the fuel state, oil pressure, oil temperature, GPS and any other instruments that rarely change every few seconds. High mileage riders have subconsciously developed a scan that incorporates all the necessary items into a semi-rigid pattern that repeats often enough to give them an excellent perception of elements.

COMPREHENSION OF ELEMENTS

To paraphrase Keith Code in his book A Twist of the Wrist (published 1983, revised 1997), “You only have so much concentration. You will spend most of your concentration on that which you know the least about” – or, as I like to add, that which you perceive as presenting the most danger. That being the case, not only is it easy to fixate on something that is a danger, but in doing so, ignore information warning of other potential dangers. A disciplined scan will avoid this trap by forcing us to continually look at new information from other sources while at the same time monitoring the information we are most concerned about. Referring back to Photograph B, we would clearly want to make the primary focus of our scan the oncoming car, as a sudden change in direction by the car could quickly put us in serious danger. However, we still need to check Zone Right and Zone Left for changes, if for no other reason than to know what our options are in case we have to take avoiding action.

Photograph B

We also obtain quite a bit of information by using our peripheral vision. It is not a specific part of our scan, because our eye can only distinguish detail near the center of our vision. However, it can still warn us of large, bright or movement-specific potential dangers well before we have to look directly at them. As Photograph B shows, our peripheral vision indicates there is a large field to the right with nothing in it. This reduces the number of items we have to specifically scan. It has been shown that successful motorcycle racers and pilots have excellent peripheral vision, which is a big help in minimizing the number of specific items required in a disciplined scan.

For the motorcyclist, instead of the pilots’ phrase “speed is life, altitude is insurance,” I would use the phrase, “situational awareness is life, riding proficiency is insurance, good riding equipment is premium life insurance” – or some variation.

Being able to anticipate likely conditions well before we need to act on them allows us to take action that either eliminates or minimizes any danger, or perhaps maximizes the pleasure. Sometimes our knowledge database helps us to see conditions before they are actually visible, whether by knowing where to look or knowing what to look for. For instance, seeing a trail of antifreeze in our lane may provide warning of a vehicle stopped in the road around a blind corner.

If our knowledge database is blank, as with a new rider, we are constantly reacting to something new. Once we have ridden sufficient miles to have a decent-size database, we have some idea of what to expect. This helps us to be ahead of the game most of the time. Unfortunately, this can also lead to a bias, in which case being prepared for what we expect may actually precipitate an accident if something else occurs. We can’t afford to let our biases and expectations overrule the information we get from our scan. If we are specifically looking for a stalled vehicle, we could easily miss a patch of sand hidden in the shade right in our travel path.

PREDICTING A FUTURE SITUATION

One of the benefits of high mileage is knowledge of conditions and what to expect. This can also be a disadvantage at times. Our knowledge is really a database of information telling us what is the most likely thing to expect under certain circumstances. For instance, in Photograph C we might expect that the fence continues on around the curve into the next straightaway, when in fact it stops halfway through the curve at the intersection of a side road. In reality, with a given set of circumstances, any number of things can occur, with the probability of each being shown by the familiar bell-shaped curve from statistics. If we are so biased in our expectations as to think only one thing can occur, we are setting ourselves up for a failure if one of the other options actually does occur. In other words, always expect the unexpected.

Photograph C

In order to minimize the risk of misperception, pilots use a system to cross reference and corroborate (or refute) individual pieces of information. This is sometimes called triangulation. In general, this means that there needs to be three indications of a condition before one acts on it – except in an emergency. A good example is in navigation. If you see a sign that says “Ellensburg” and an arrow pointing to the right, you don’t automatically turn right based on the sign alone. You only turn right if you see there is a road there, the road goes to the right and it goes generally in the direction of Ellensburg. If any of these are missing, you continue scanning until you have corroborated or refuted the initial indication.

It would seem obvious that if you see a truck coming across the center line and heading for you, it is not necessary to find three corroborating pieces of information before you take action to avoid the truck.

I divide all situations I perceive into four levels of urgency.

- LEVEL 1: I expected it to happen, and the scan confirmed my suspicions. Very little, if any, avoiding action was required. I might even mentally pat myself on the back for being so alert.

- LEVEL 2: My scan may have caught the hazard a little bit late, or perhaps another vehicle made a sudden, unpredicted move requiring specific avoiding action, but not so late that I didn’t have time to utter a few expletives or display the Universal Hand Gesture of Ill Will.

- LEVEL 3: Caught me so much by surprise that I was totally focused on survival – brakes, clutch, throttle, shift and where do I go to be the safest. When this happens, it is invariably because I wasn’t paying enough attention.

- LEVEL 4: I don’t imagine I’d be around afterward to discuss a Level 4 situation.

That completes the basics of situational awareness. As each of us looks back on our last year of riding, if there were more than three or four Level 2 emergencies or one Level 3 emergency, I would suggest there needs to be more knowledge in the database, better situational awareness or both. Slowing down also helps. Regardless, improving our scanning process will go a long way towards improving our “sierra alpha.”

Remember: safety begins with your attitude, and attitude is everything!

Author: Clayton Canfield #116551

References:

WIKIPEDIA PAGE: SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

See “DEFINING AND MEASURING SHARED SITUATIONAL AWARENESS,” by Albert A. Nofi

Photo by Gerhard Siebert on Unsplash